Citation

Park, Y., Nakamura, J., Rush, J., & Fuxman, S. (2020, June 2). Supporting students experiencing trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Regional Educational Laboratory Appalachia (REL AP).

Abstract

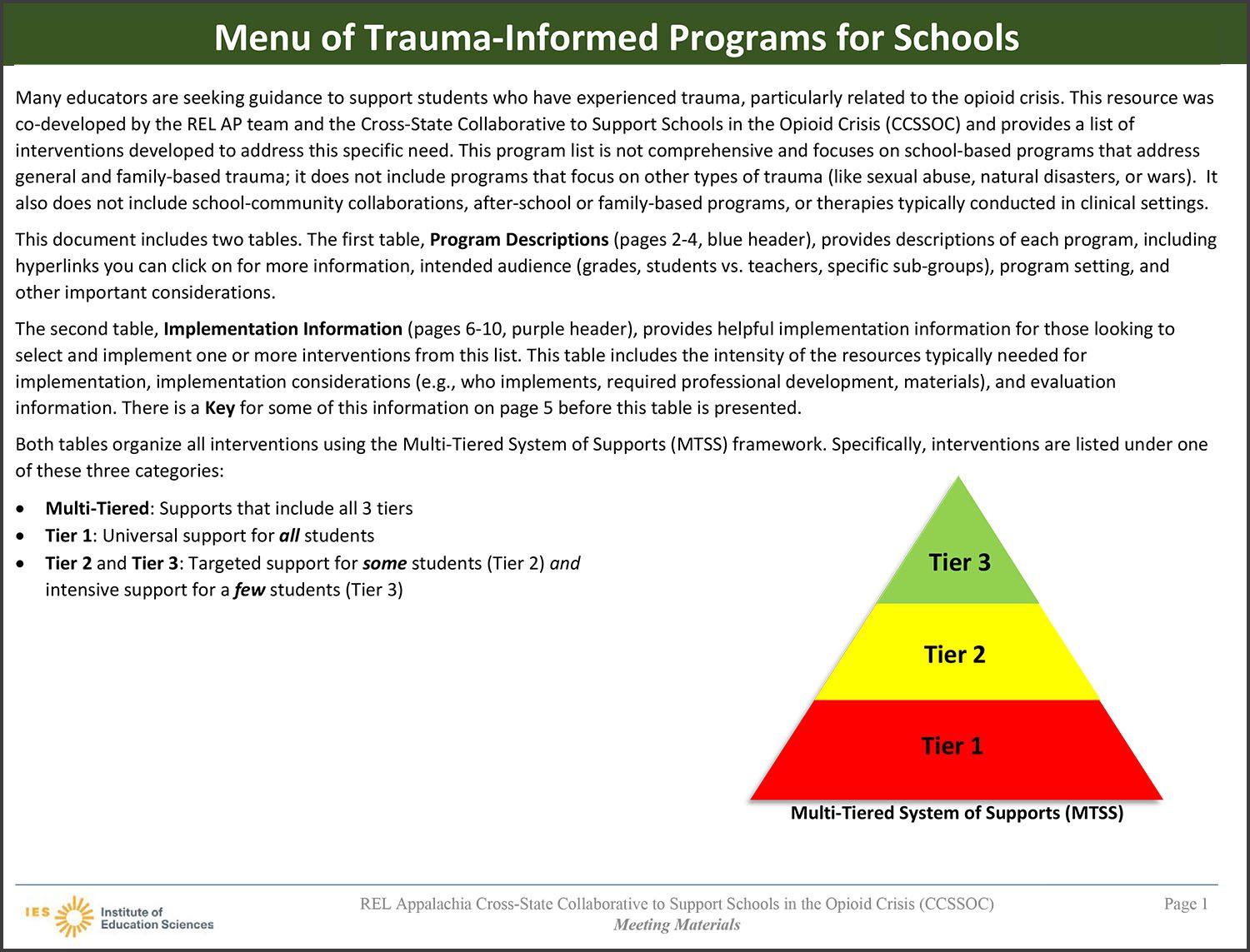

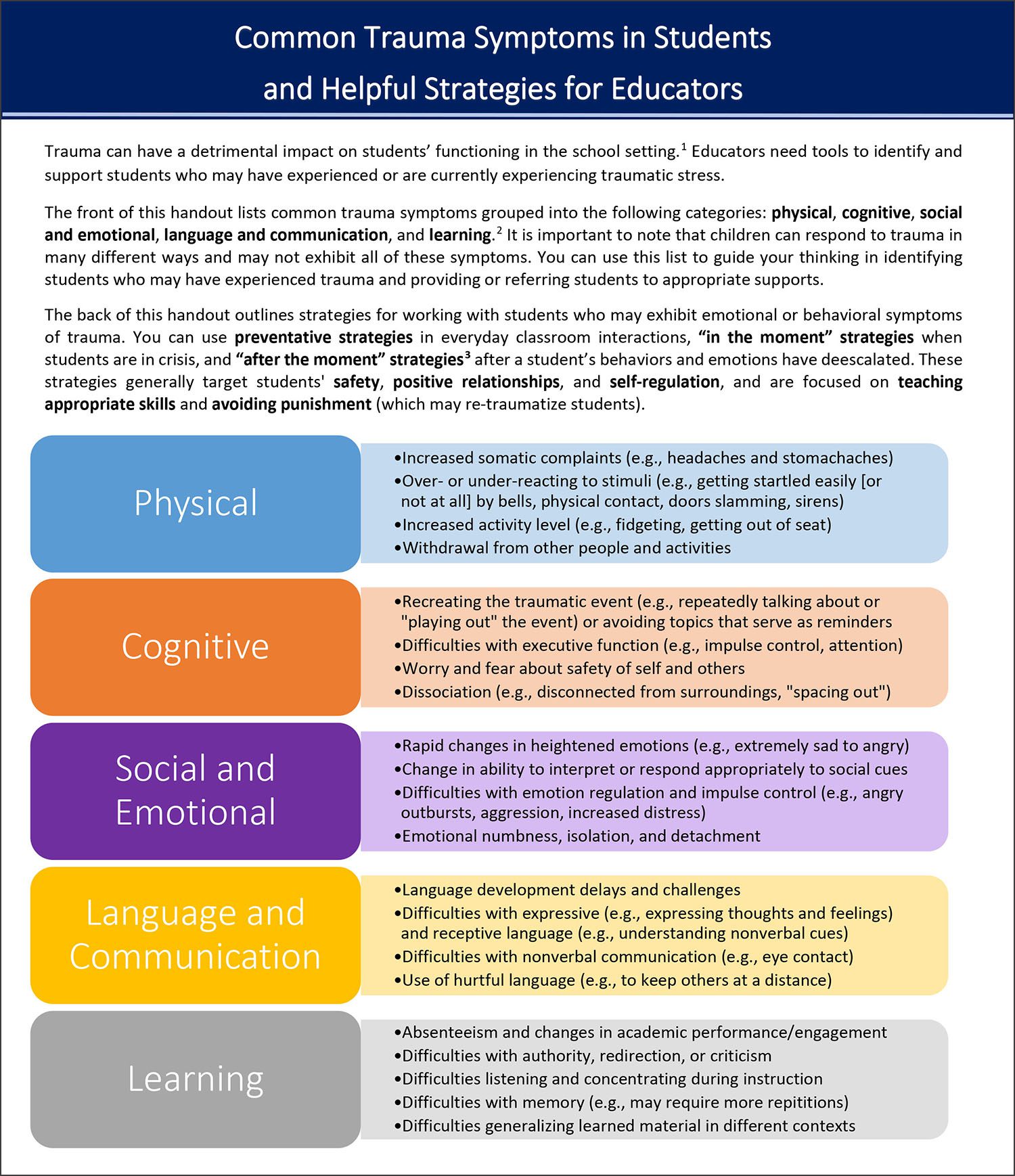

For many students, the COVID-19 pandemic is compounding traumatic experiences for diverse reasons, such as potential increased incidents of neglect, abuse, and isolation. At the same time, educators are limited in how they can support their students while school are closed. In the Appalachia region, this new wave of stressors comes on top of the traumatic experiences students are experiencing related to the opioid epidemic. Family and community opioid use has devastating impacts on children and families, especially in this region, with about 170,000 children experiencing a range of stressors and trauma related to parental opioid use, such as losing a parent to an opioid-related death, having an incarcerated parent due to opioid use, or being removed from their home due to an opioid-related issue. 1 REL Appalachia (REL AP) has been working with key stakeholders from the region in state and local education agencies, departments of health, community-based organizations, and universities to identify best practices for addressing student- and educator-related trauma through the Cross-State Collaborative to Support Schools in the Opioid Crisis (CCSSOC). Through this work, the collaborative developed and curated tools and strategies all educators may find useful when supporting students during this time.

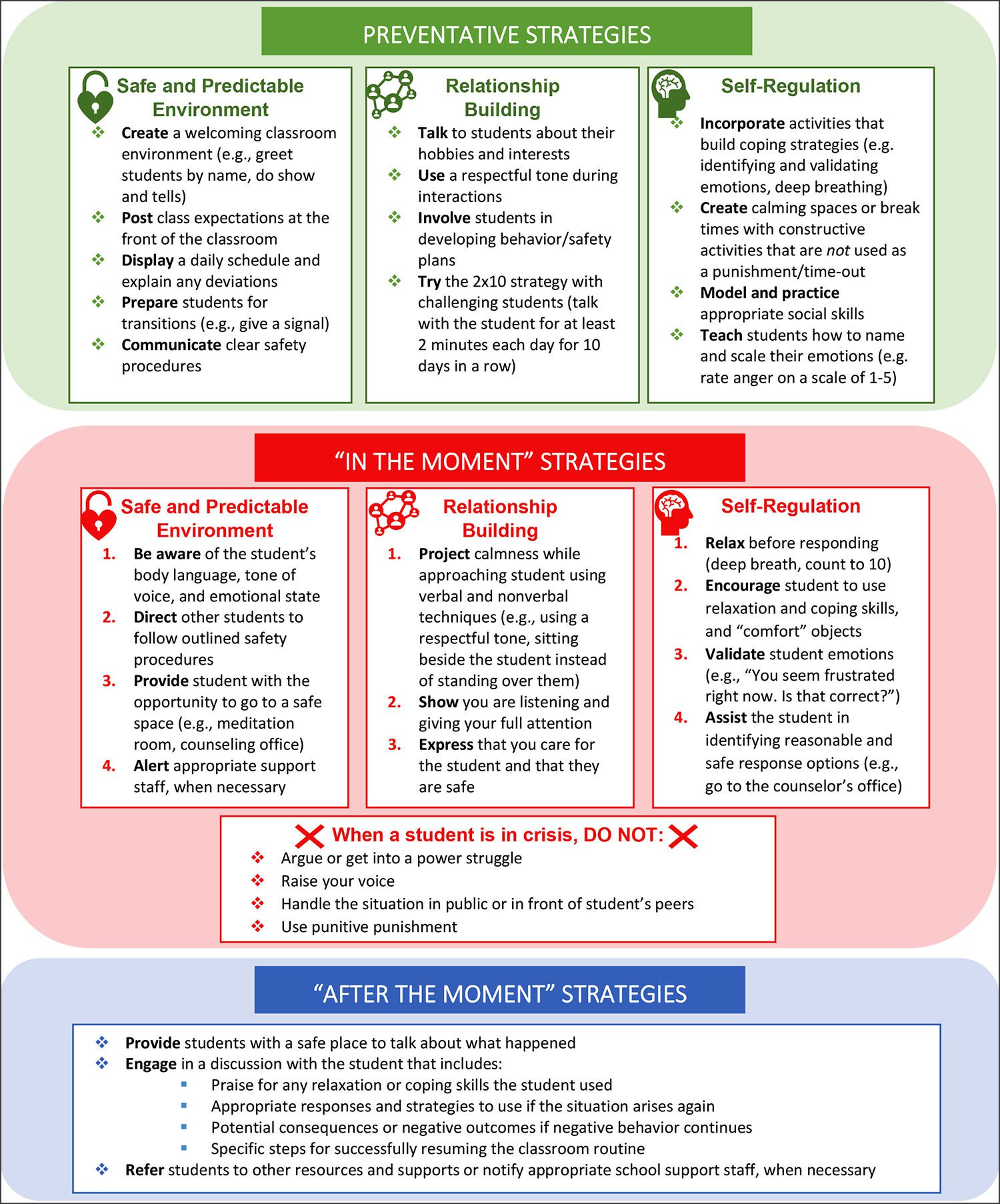

The handout provides information about the common symptoms of trauma, grouped into five main categories, 2 as well as everyday strategies 3 that educators can implement in the classroom to support students exhibiting symptoms of trauma.

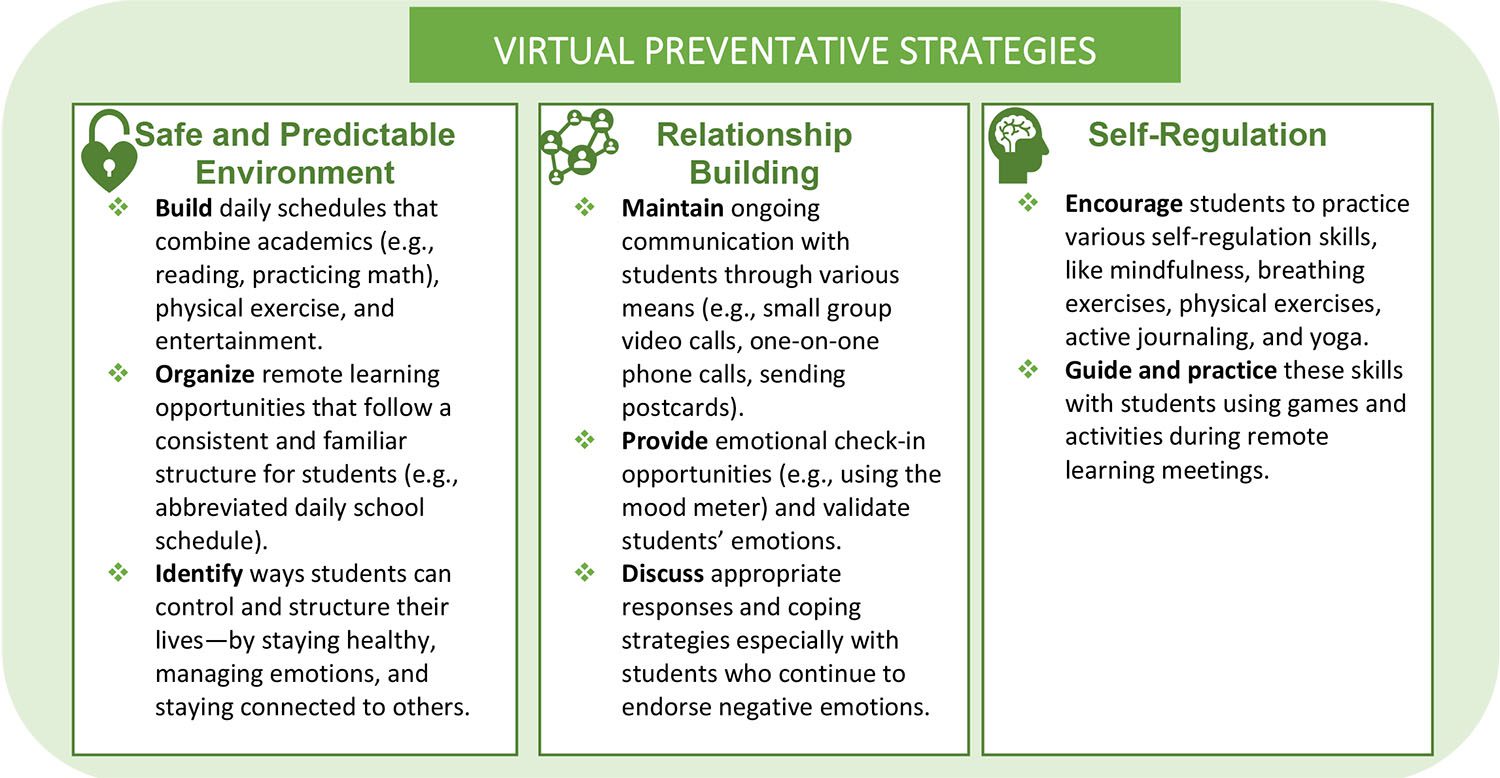

Everyday strategies in virtual settings In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we adapted strategies from the handout to help educators address student’s social-emotional and mental health needs associated with trauma in virtual settings:

- Provide structure and routine: Educators can work with parents to ensure that students have proper structure and routine—a critical need for students who experience trauma. One strategy is to work with families to build daily schedules that combine academic enrichment (e.g., reading, practicing math), physical exercise, and entertainment. Educators can also promote structure on a macro-level by organizing remote learning opportunities that follow a consistent and familiar structure for students, such as an abbreviated daily school schedule.

- Promote a sense of control: Students’ resiliency increases when we help them increase their locus of control—the extent to which they feel in control of their own lives. To do so, educators can work with students to identify ways they can control their own lives —staying healthy (e.g., maintaining social distance), managing emotions (e.g., practicing mindfulness), and staying connected to others (e.g., connect with friends and relatives by phone).

- Be present: In this period of time, perhaps more so than ever before, students who have experienced trauma need to feel the support of trusted adults in their lives—including their educators. Educators can maintain ongoing (e.g., weekly) communication with students through various means: small group video calls, one-on-one phone calls, sending postcards, etc. The primary purpose of these interactions is to convey to each child that they can continue to emotionally lean on their educators even when school buildings are closed. For more information on relationship building, see Virtual Relationship Mapping (source: Harvard Graduate School of Education) which provides strategies and lesson plans for school administrators and staff to make sure that every student has a supportive adult mentor at the school.

- Provide emotional check-ins: During virtual interactions, educators should provide students with emotional check-in opportunities (e.g., using the mood meter; source: National Association for the Education of Young Children, NAEYC) and validate students’ feelings. Educators should praise students for using relaxation or coping strategies. In addition, educators can follow up with students who endorse negative emotions, especially if they are noticing that this is becoming a pattern, and discuss appropriate coping responses and strategies to use in such situations.

- Strengthen self-regulation skills: Students (and adults) can develop skills to regulate their own emotions. As with any type of skill, self-regulation skills need to be learned, practiced, and then practiced some more to achieve mastery. These skills include mindfulness, breathing exercises, physical exercises, active journaling, and yoga. Educators can guide and practice these skills with students using various games and activities ( source: Stop, Breathe, & Think) during remote learning meetings. Educators can also refer students and families to various apps and games; for example, see this collection from Common Sense. Educators can also help parents and caregivers make an at-home schedule with various activities to practice these skills with their children; see this blog post from the Children’s Hospital of Orange County on how parents can schedule and spend one week focusing on building these skills with their children.

These strategies, as shown in the Virtual Preventative Strategies infographic below, can be appended to and used together with the “Common trauma symptoms in students and helpful strategies for educators” handout. Download the Virtual Preventative Strategies infographic here.