SRI’s work on an Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) program is advancing our ability to identify potentially dangerous chemicals in the air.

When it comes to detecting gasses at a distance, we now have a highly functional set of tools, including optical gas imaging and laser-based systems. These tools allow oil and gas companies, for example, to detect methane leaks from a safe distance.

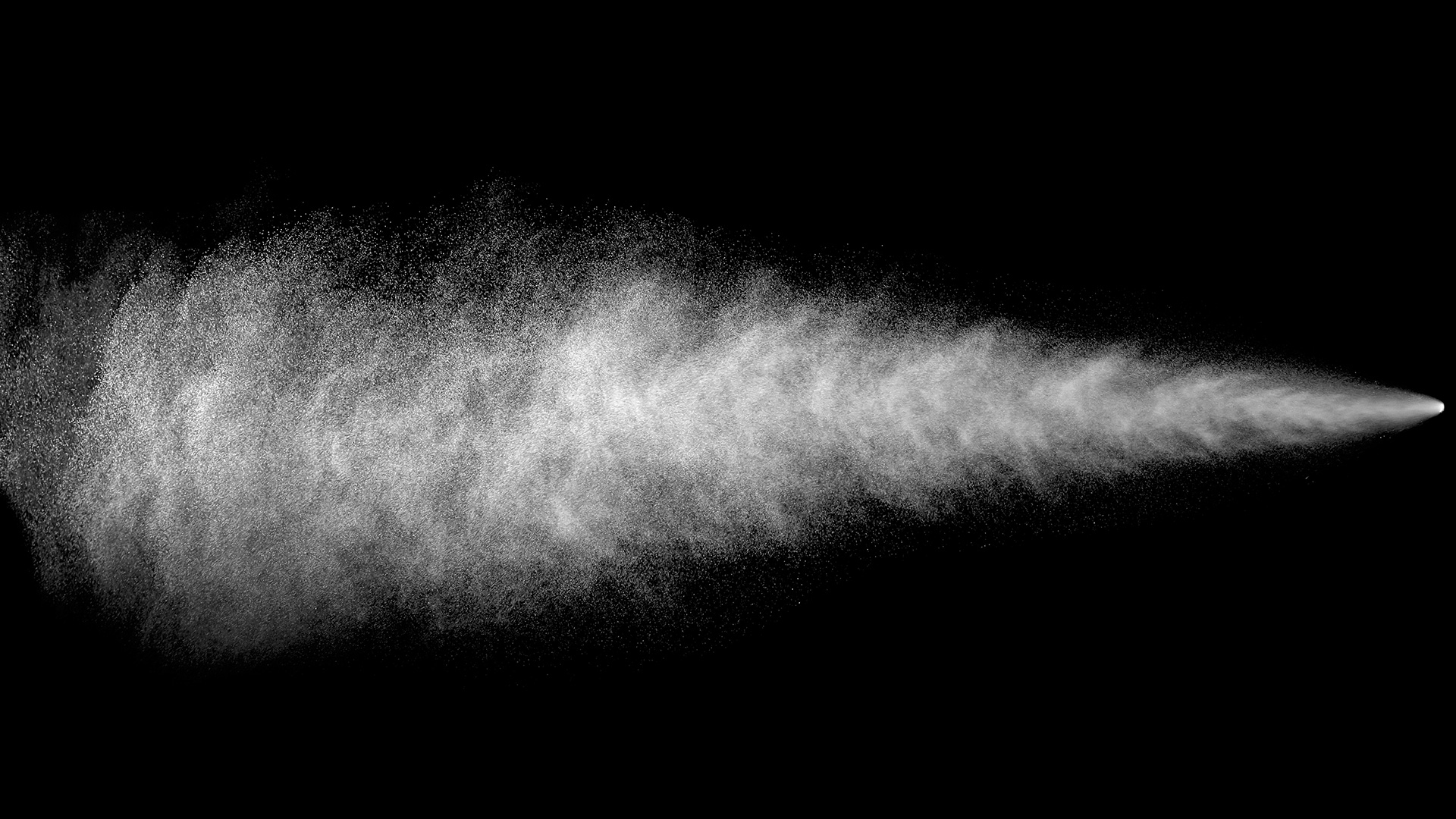

But detecting aerosols — that is, liquid or solid particles suspended in the air — is a much more challenging problem. The issue, explains SRI program director Jason Tyan, is particle size. Because gas molecules are consistent, they are easy to detect and classify. Aerosol particles, on the other hand, vary greatly in size, which alters their spectral signatures and makes them notoriously difficult to identify.

Numerous dangerous materials — from powdered fentanyl to chemical warfare agents — can spread as aerosols. These environmental risks led the IARPA to initiate the PICARD program, which has aimed to “develop a fieldable sensing platform for the rapid identification of aerosol particles with complex chemical and physical characteristics in challenging environments.”

“The challenge of this program is to detect low-density chemicals at a long distance. Sensitivity is the issue, because you can only detect a very small signal.” — Jason Tyan

The initial results of SRI’s work on this program demonstrate rapid advances in our ability to detect and identify aerosols at a distance, pointing toward future applications that may save lives during unintentional releases of hazardous chemicals and even intentional attacks by nefarious actors.

Building an aerosol detector that works

To overcome the current limitations of long-distance aerosol classification, the SRI-led team built a hardware and software solution that relies on both active (laser) and passive (hyperspectral imaging) sensing.

In isolation, both types of sensors have disadvantages when it comes to detecting aerosols. Information from infrared imaging sensors is too imprecise to identify the chemical composition of aerosol plumes. Lasers, on the other hand, bring additional precision, but they also need to find a strongly reflective background to return meaningful information.

“The challenge of this program is to detect low-density chemicals at a long distance,” observes Tyan. “Sensitivity is the issue, because you can only detect a very small signal.”

SRI’s solution addresses the sensitivity challenge by combining two complementary sensing modalities: active laser and passive imaging. The passive sensors (a long-wave infrared hyperspectral imaging camera and a low-light visible/near-infrared camera) detect the shape and relative concentration of the aerosol plume and collect information about the surfaces of opportunity (SOOs) within the natural background. The spectral signatures from the passive sensors are then used to optimize the targeting of the laser (active sensor) and collect detailed scattering information about the aerosol particles.

“You can’t just shoot the laser through the plume and hope for the best,” emphasizes Michael Isnardi, a distinguished computer scientist at SRI. “It needs to hit something so the photons come back and provide a reflectance spectrum that contains the signature of the chemical or chemicals you’re trying to analyze.”

The system can then compare the incoming data from both the active laser and the passive imagers to a pre-built “spectral library” of target compounds to identify the presence of specific target chemicals. Underneath the hardware layer, SRI is also building a custom machine learning algorithm that further improves the system’s ability to reliably classify aerosols.

Breakthrough results in aerosol detection

The SRI team successfully demonstrated the proposed technology approach through both internal and external testing and evaluation. The system was able to detect certain chemicals at standoff distances of up to 110 meters and is capable detecting and identifying more than 100 chemicals at closer standoff distances — including toxic fentanyl analogs and warfare agent precursors — at concentrations as low as 0.2 mg/m³.

The custom machine learning model the team is building for the system, meanwhile, is showing great promise in tests based on simulated sensor data, particularly when it comes to accounting for complications like spectral distortions and poor surfaces of opportunity.

“We believe we have met and exceeded our Phase 1 performance goals, as confirmed by the government’s testing and evaluation results,” says Tyan.

“There are some very compelling applications for a device that can detect aerosols at a distance, from monitoring suspected drug laboratories to tracking illicit dumping of hazardous material to developing early-warning systems for chemical warfare agents and incapacitants.” — Jason Tyan

There are certainly some obstacles, Tyan notes, between the current state of the art and a fieldable system. “In the long-distance range, there are more environmental factors we have to consider, like humidity, temperature, and wind,” he cautions. “That information will need to be incorporated into our sensing system, which means an additional layer of ambient sensors.” Speeding up the system’s passive sensing capabilities, he adds, will also be important when it comes to building a system appropriate for deployment in the field.

If these initial findings can be matured into a fieldable device, the advantages are clear. The SRI team sees drug enforcement, industrial monitoring, domestic counterterrorism, and environmental security as areas where aerosol detection could play a key role in improving our safety through better situational awareness.

“There are some very compelling applications for a device that can detect aerosols at a distance,” concludes Tyan, “from monitoring suspected drug laboratories to tracking illicit dumping of hazardous material to developing early-warning systems for chemical warfare agents and incapacitants.”

To learn more about SRI’s work on aerosol detection, contact us.

Supported by the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) via Department of Interior/ Interior Business Center (DOI/IBC) contract number 140D0424C0007. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright annotation thereon. Disclaimer: The views and conclusions contained herein are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of IARPA, DOI/IBC, or the U.S. Government.